Burden Of Command is a lot like me, in that it deserves a lot of love but it’s too frustrating and annoying to get it for long.

The concept is promising: tactical battles with a small batch of soldiers, but as a “leadership RPG” instead of a regular wargame. Occasional glimpses kept my hope alive over its long development, perhaps predisposing me to forgive more than usual when it finally arrived last month. I’m glad I did. But wow, did this game get me yelling for a while.

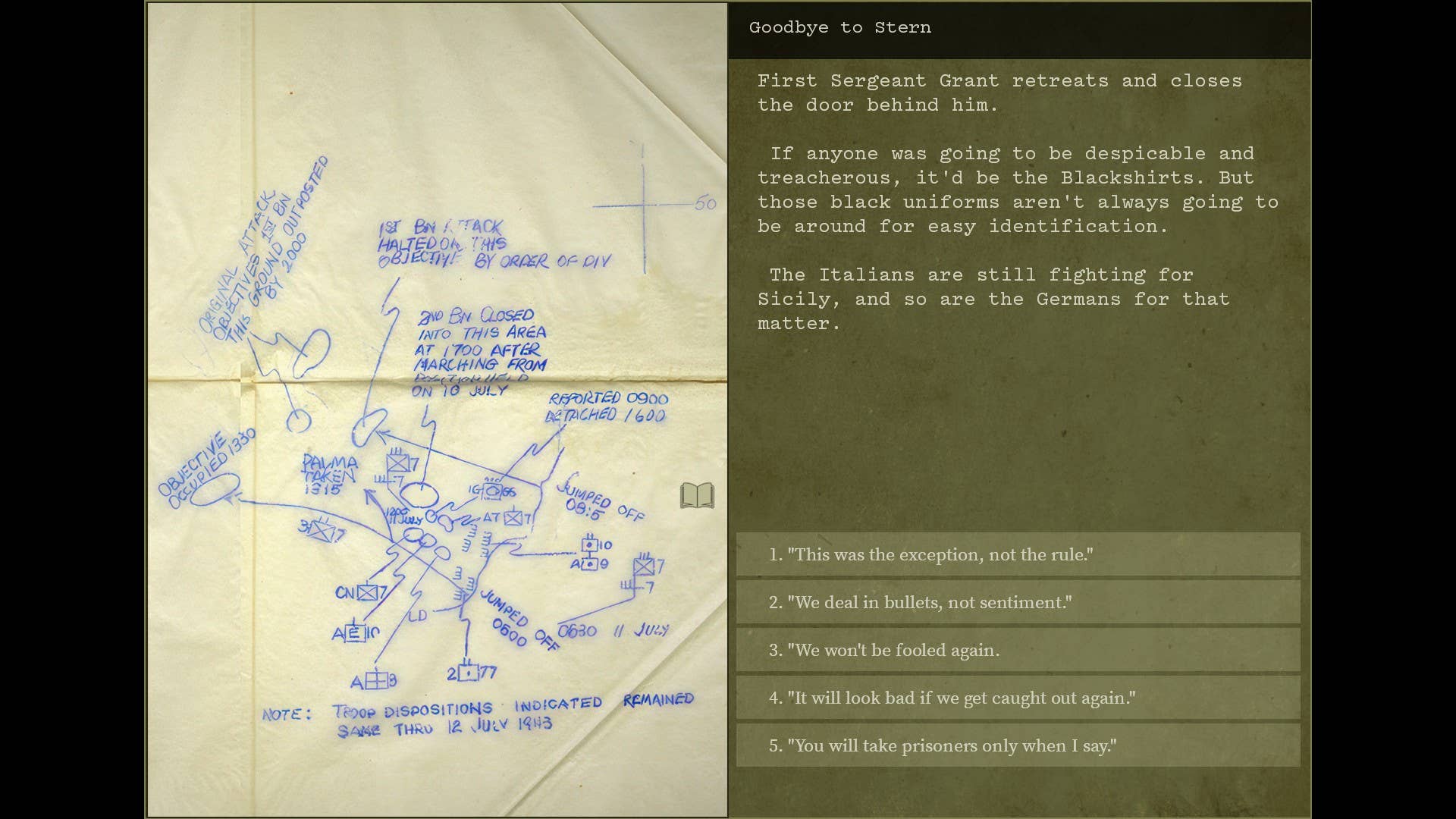

You are a newly hatched lieutenant of the US Army, ready to respond to Hitler’s genius big brain declaration of war by repeating and debating his ideas. But you’ll be fighting in Italy first, and in Sicily before that, and in Morocco before that. And before that, you’ll finish training. Before that… you’re a blank slate.

This isn’t the player character as the most special person in the world. It doesn’t matter who you were before. Training is a natural tutorial, but also a section that’s already defining you. Moreover, it’s trying to get you to accept mistakes. To learn by making them. When you screw up by not understanding the order system or how turns work, that’s intended, I think, to put you in the position of your character. He hasn’t played 300 hours of wargames this year, or watched all the films and convinced himself he’s a tactical genius. When you fumble with the UI, that’s him conveying his orders badly, or getting flustered by adding physical pressures to book learnin’.

But it draws up my perennial, whingeful cry: Burden Of Command is a single-save game. Worse: that save is overwritten with every action. Move a squad three hexes and it saves, I suspect, after each one. Certainly, the constant pauses suggest more than just updating how many mines you’re standing on. Micro-delays that rob battles of some tension, but worse: everything is final.

BoC makes a point of this – this is roleplaying as being this guy, not maximum numbers and ideal outcomes. You’re expected to fail, to get named characters or even yourself killed, to retreat or lose, and continue with events altering course (a rare and precious dynamic worthy of respect). One event warns of an upcoming graphic image, which you can skip by having your guy look away.

But that’s undermined by its interface, and the opaque details of how things work. UI elements deactivate when you check something else, causing squads to shoot instead of capturing. Icons and panels appear and disappear in awkward ways. It’s hard to see the tiny icons over units you can’t zoom into enough (a real shame; I like the art). Units deselect when you drag the map, and movement ranges are only shown for the current action, exacerbating unclear rules that throw up inconsistencies I can’t explain. I can move three hexes over that grass but only two over identical grass? Rather than charge a hex westwards, my guys run downhill and attack back up it again? And squads block each other’s movement – a forest can fit twelve guys, standing room only – which isn’t indefensible, design-wise, but “My men run three hexes under fire because my other men won’t let them pass” isn’t a satisfying narrative consequence of my actions. And there is not, I say calmly with calmness, any order confirmation. Even ending the turn doesn’t ask, and that’s bound to the space bar.

The relationship between “orders” and “actions” throws up curveballs, frustrating Burden’s most simple-yet-rich system. Turns are divided into rounds. In each round you choose a lieutenant, whose order points are spent to move, act, and activate squads under him. Each squad can only use its own action points if it’s activated, but can act independently afterwards. You must end the round to use another officer, but the next round goes to the people who are just asking questions. It’s a game of prioritising, and distributing your focus to where limited orders are most needed, made more malleable by several details. Officers can have multiple rounds, if you want to move Thompson’s first squad out of danger, fire Stern’s machine guns, then move Thompson’s other squads. The Captain can act whenever you want, activate any squad, and use Bolster and Rally actions on adjacent hexes. Lieutenants must be in the hex to do that, which carries other benefits. But officers move faster alone, and are just as vulnerable to explosions (life tip). Suppressed/demoralised people lose actions/orders, so sending one into the breach could paralyse his whole platoon, as they’re left without anyone telling them to stop waving at the guys with Very Real Concerns and shoot them.

They’re often needed elsewhere too, as Bolster and Rally (and Press: spend one order to restore one action) are always needed. One is an all-purpose “do everything better” power, the other lifts suppression. They’re not special perks on a cooldown. They’re bread and butter, a constant reminder that you’re not here to do Tactics or add +4 to attack and fire damage. It’s leadership as what men in combat need: being there. Taking charge, prompting training to kick in. A whole round might be running back to an immobilised squad just to be the guy. Maybe he’s being a dick, maybe he’s supportive, maybe he’s playing the bagpipes, but he’s here. We’re all here, let’s go.

It’s a decent shot at simulating human limits to organising in a deadly situation. But it’s sometimes opaque, and prone to bugs and inconsistencies (WHY does that suddenly take two orders? Why is he suppressed, nothing has happened? Why did my officer not move with that squad?). And of course, your save is constantly overwritten, leaving you unable to enjoy the consequences, because those weren’t your decisions. I would have quit outright after a few hours, if it didn’t quietly keep a backup save once per turn.

Burden Of Command isn’t here to punish you, though. Gunfire almost never wipes squads out, but holds them down until someone charges, usually causing surrender. Deaths were rare until the Germans showed up, barring a bug that vanished most of a squad, leaving them genuinely useless even months later (it wasn’t worth the cost in abstract points to replenish them, so they sat unmoving at various starting areas for most of the war. The remaining squads got more attention from Lt. Daddy and they turned out fine, dunno what your problem is). The point isn’t a gruelling hardcore challenge or showing off. It’s how you handled the job, the ordeal.

Its flaws distract from its great strength – it is, essentially, complex interactive fiction. When not in battles, you’re reading through events around them, handling antics from the men, writing letters to soon-to-be-grieving families. There’s esteem of men and brass (not opposed, but the latter mostly want strategic results, while the former want to survive) to earn, your own wellbeing, and relationships with other officers to balance against preparing for the next fight, and doing the right thing. The writing is quietly excellent, with a slight stoicism that never veers into jingoism, handwringing, or war porn. Tonnes of research went in, but an impressively restrained hand left the bulk of it out of shot (“So it goes.” – Archivist Ed). The result is an authenticity of spirit rather than technicality, and succinct text that nonetheless conveys what it ought to. It trusts the audience to understand and infer things, which is worth the cost of occasionally going over my head, resulting in the classic RPG dialogue problem of responses not quite meaning what I thought.

I’m struck too by how much work clearly went into the permutations. Some scenes are “Crucibles” wherein your responses determine which of eight “Mindsets” you espouse, but may cause unpredictable reactions in other officers. Thompson might be inspired by your Idealism, but Wilson develops Caution against such naïveté. It’s sometimes dissatisfying, as your first Mindset permanently locks another three that seem compatible. This may be for balance, since developed Mindsets grant abilities of varying utility. Many are once-per-mission actions, landing squarely in the “too useful to use” zone. That’s still preferable to making them all-important though, and many passives are too subject to chance to be more than a pleasant surprise, in a way that fits Burden’s ethos more than the standards of its genre.

This is not a game about customising a perfect team, see. You’re one leader among many, not a Shepard among sheep. I turned down a free advantage before one mission, doubting I’d use it, so it should go to some other rando. I didn’t expect a videogame payoff, but decided as someone in that position.

Burden Of Command is no heavy melodrama of traumatised war lads (despite the occasionally audible Shane Taylor, aka sad soldier boy and my dear son Doc Roe), but is about people rather than game tokens. I even got over my initial hatred of Lt. Dearborn for his platoon repeatedly embarrassing me in training by failing some hidden “morale” check to move, wrecking multiple turns. He had low “trust”, see, and experience, thus a higher chance of spending orders on nothing. I wanted to have them all shot. But his multilingualism was an asset, and he grew into an oddly loveable, conniving stalwart whose men I’d put on the vanguard if I had any bloody control over where anyone starts.

If there’s a summary of Burden of Command, it’s exactly that. A maddening few hours of inconsistent behaviour and unclear details compounded by an intrusive save system, slowly giving up ground to the excellent, unusual, and replayable narrative RPG it’s trying to be.