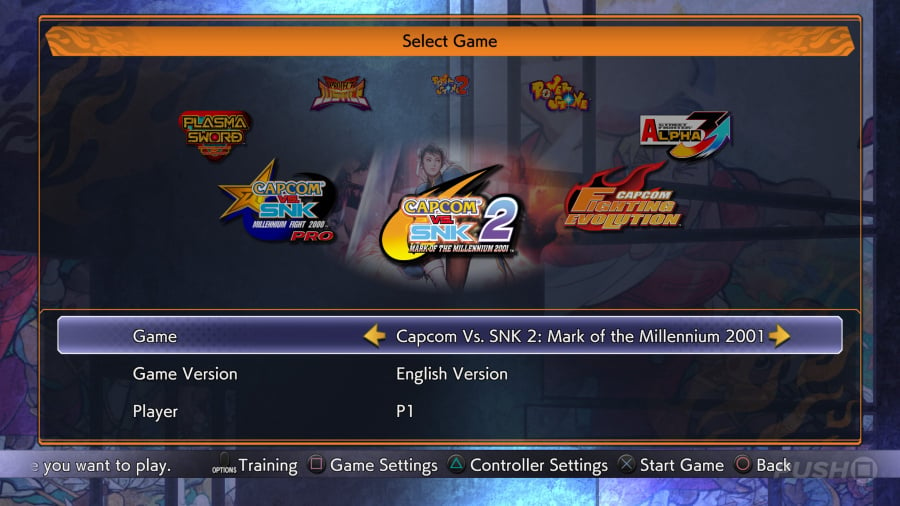

Where its predecessor largely focused on DarkStalkers – including a couple of titles which never released outside of Japan – Capcom Fighting Collection 2 mostly turns its attention to SEGA’s infamous NAOMI arcade board, so we’re looking at a compilation of mostly Dreamcast-era brawlers here.

If you’ve played Capcom Fighting Collection or Marvel vs. Capcom Fighting Collection: Arcade Classics, then you’ll be familiar with the presentation: you can toggle between Japanese and USA ROMs at will, quick save your progress, and explore hundreds of gallery items, spanning everything from concept art through to hand-written design documents.

Crucially, all of the games have also been enhanced with rollback netcode, although we should stress in the pre-release review environment we weren’t able to properly put this through its paces. It also should be noted that there’s no crossplay between consoles, which dramatically reduces the potential player pool you may be able to find.

But from our experience, the emulation is rock-solid, with a variety of different personalisation options pertaining to simulated scanlines, aspect ratios, and so on. It’s worth adding that in all cases you’re getting the arcade versions of these games, so any additional home console modes – like the World Tour in the PS1 version of Street Fighter Alpha 3 – are absent.

Due to the multi-game nature of this release, and the sheer variety of the content included, we’ve decided to breakdown each game individually for this review.

While it certainly wasn’t the original Capcom and SNK crossover, we suppose you could argue Capcom vs. SNK: Millennium Fight 2000 is the first one to really matter. Presented here as part of its expanded Pro re-release, adding Dan Hibiki and Joe Higashi to the roster, this 2001 effort brings the best of King of Fighters and Street Fighter Alpha under one roof.

Highlight gameplay systems include the Groove mechanic, which alters the way the Super meter works depending on your personal persuasion. It also adds a slightly unbalanced Ratio system, where lowly fighters like Sakura take up one spot and more beastly opponents like Evil Ryu can occupy up to four. It means you’ll need to think relatively carefully about the best way to compose your team.

The sprites are chunky and well-animated, while the backgrounds are beautifully illustrated and incorporate 3D elements to help bring them into a more modern era. We’re particularly fond of the transition animations which trigger between these stages; ground-breaking at the time, they have a kind of kitsch-like appeal when appreciated from a modern perspective.

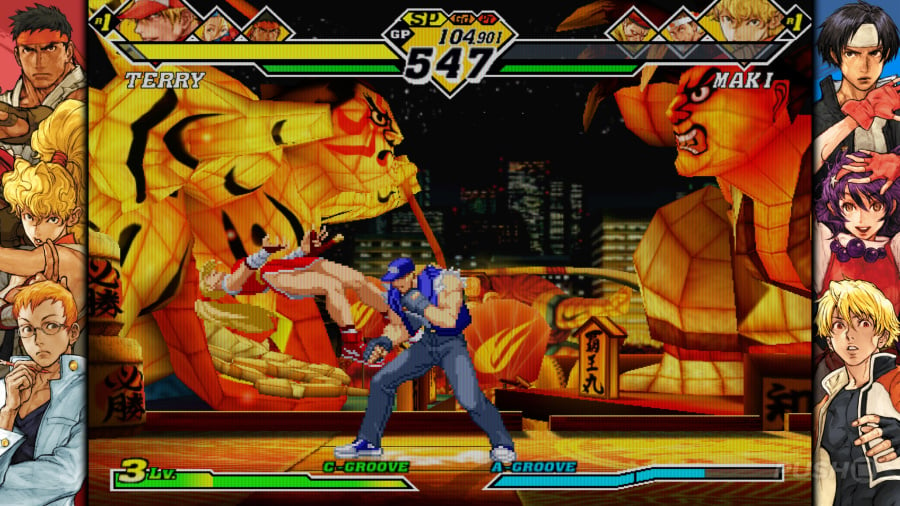

Among the best ever sprite-based fighters, Capcom vs. SNK 2: Mark of the Millennium 2001 improves on practically everything from its already likeable predecessor, aside from perhaps the stage introduction animations.

Switching from a four-button control scheme to a more familiar six-button system, this blows out all 48 characters’ arsenals, and incorporates six different Groove styles to augment almost unlimited variety. These mechanics are inspired by everything from Street Fighter 2 to Samurai Shodown, and change more than just the Super meter, but also the fundamental fighting mechanics.

Taking full advantage of SEGA’s NAOMI hardware, this game substitutes the gorgeous pixel-based backgrounds from its predecessor to fully rendered 3D stages, similar to those in Marvel Vs. Capcom 2: New Age Of Heroes. Personally, we don’t think they’ve aged anywhere near as well as the previous game, but there are some undeniably neat Easter eggs and fun distractions.

Our only real criticism of this game, which was also a complaint at the time, is how it recycles the sprites of some character models from ancient releases, like Morrigan from DarkStalkers. Compared to the new models created bespoke for this release, there’s a lack of overall consistency to the art which prevents it from achieving true greatness..

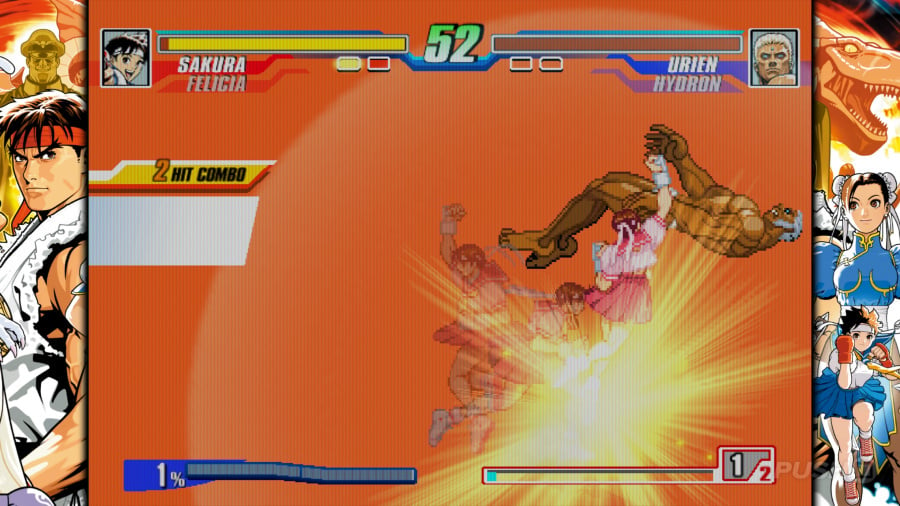

Capcom’s legacy may be stacked with all-time classic fighting games, but Capcom Fighting Evolution – also known as Capcom Fighting Jam – was a rare misfire for the publisher. It also represents a low-point for this compilation, even though we think it’s ballsy of the Japanese publisher to include it.

The game started life as a 3D fighter named Capcom Fighting All-Stars: Code Holder, which was ultimately cancelled in 2003. It includes characters from Street Fighter 2, DarkStalkers, Street Fighter Alpha, Red Earth, and Street Fighter 3, in most cases quite literally recycling the original assets and animations – although in some instances frames have been inexplicably removed.

The backdrops are horrific; a dramatic and staggering step backwards from the stunning artwork used in the SNK crossover games. And the combat system doesn’t really work, with each character tethered to its distinctive series’ mechanics, making for an overall mess of a competitive experience.

New character Ingrid, who’s the only new sprite included here, is a cool character design – but she’ll forever be tethered to this failed fighter, which is a terrible shame.

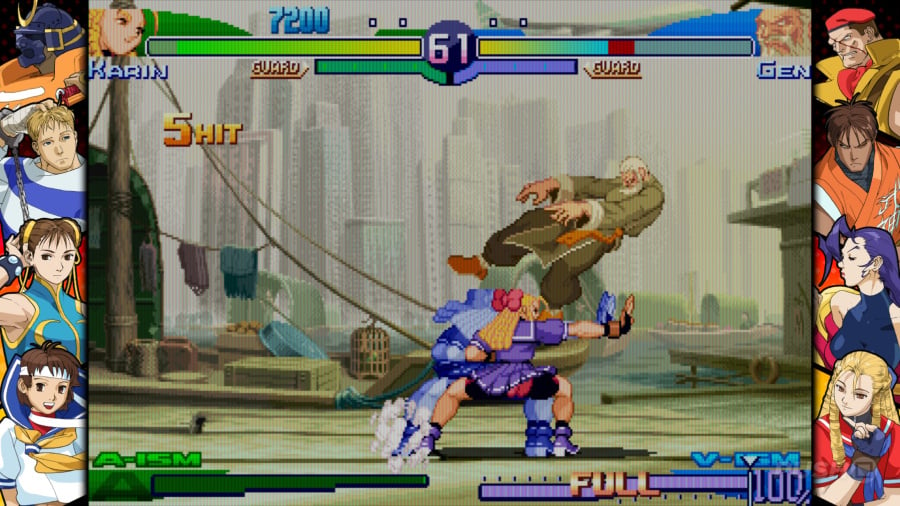

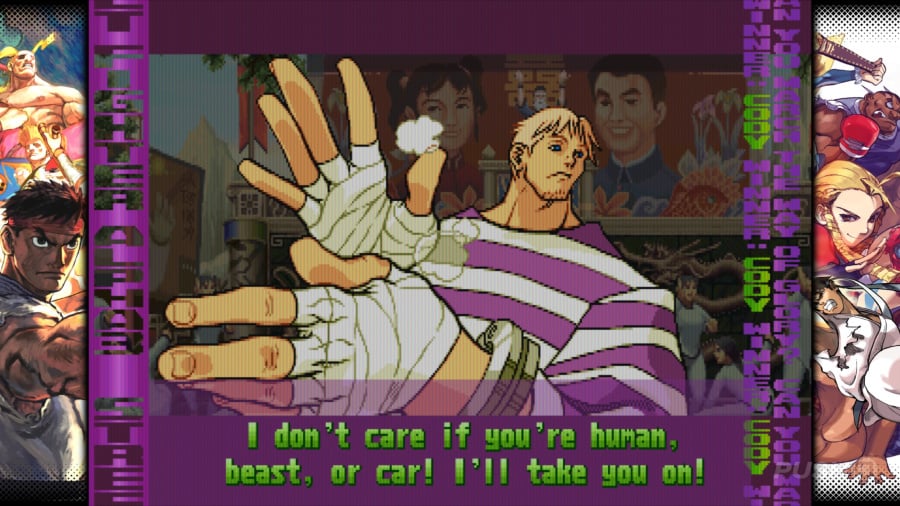

If you own the Street Fighter 30th Anniversary Collection, then you’ll already have a version of Street Fighter Alpha 3. But this Upper re-release, deployed in Japanese arcades back in 2001, incorporates the additional characters from the original home console releases, including Dee Jay, Fei Long, T Hawk, Guile, Evil Ryu, and Shin Akuma.

Outside of the expanded character roster, the gameplay largely remains unchanged. The main system here revolves around “isms”, with three different power gauges paying homage to previous Street Fighter games, each with different strengths and weaknesses. Some of these come with additional moves associated, so there’s a lot to explore and experiment with.

Perhaps the only downside here is that this still isn’t the complete version of the game, as subsequent handheld ports, including the miraculous Game Boy Advance conversion and arcade-perfect PSP release, added in even more characters, including Ingrid from the aforementioned Capcom Fighting Evolution. As the arcade release, this version is also missing the well-liked World Tour single player campaign from the PS1 port.

Unlike anything else in this compilation, Power Stone’s closest analogue is perhaps Super Smash Bros., but even then its 3D battlegrounds make it wholly unique compared to Nintendo’s mascot mash-up.

Another title developed for SEGA’s NAOMI arcade board and later ported to the Dreamcast, combatants from all around the globe duke it out in 19th-century arenas in search of the mythical Power Stones. The gameplay sees you collecting different coloured gems from around the stage in order to open up your combat arsenal, culminating in devastating super attacks.

You can also pick up weapons, ranging from swords to machine guns, making for a chaotic experience.

While the original entry is straightforward in comparison to its sequel (more on that shortly), its simplicity does have some advantages, namely its combat is more legible and the pacing is more consistent without the distraction of the boss battles and stage transitions from its more expansive successor.

It should be noted that the brilliant VMU minigames from the Dreamcast version are sadly not included in any capacity here.

Bigger, better, more bad ass is the mantra of sequel Power Stone 2, although personally we’ve always preferred the comparative simplicity of its predecessor. The sequel ups the number of players on screen to four, resulting in absolute bedlam. Stages also change over time, so you may find yourself fighting on a warship before skydiving to the ground, creating a sense of dynamism.

The traditional battles of the arcade mode are interspersed with boss fights and minigames, like the infamous Pharaoh Walker battle, which sees you facing off against a giant Egyptian kaiju. There are also way more weapon pick-ups than in the game’s predecessor, including everything from roller blades to bear traps.

The sheer chaos is unquestionably entertaining, but it’ll come down to personal preference whether you prefer it to the original game’s more reserved approach.

One thing we would add is that, as this is the arcade version, the excellent Adventure Mode from the Dreamcast edition is absent, stripping the experience of much of its single player longevity.

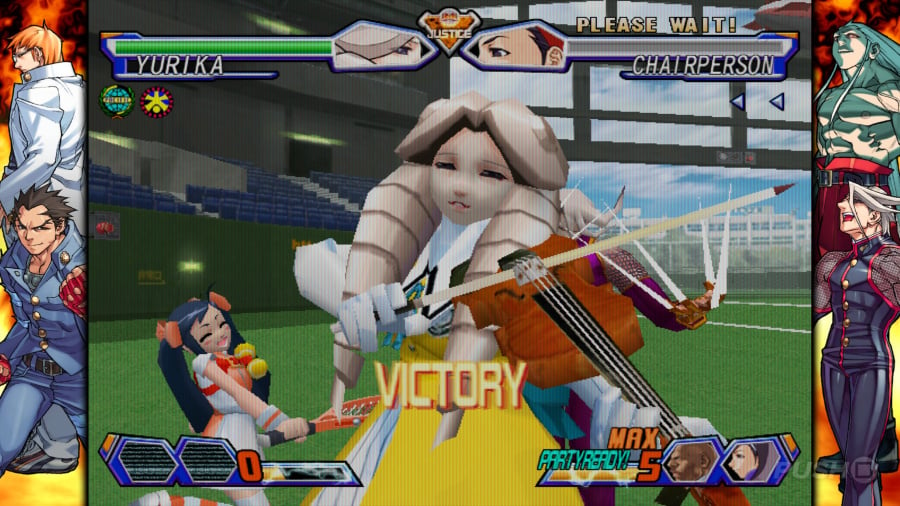

Project Justice is the second – and last, as things stand – Rival Schools game, originally released in 2000 for arcades using SEGA’s Naomi board. The original game ran on Sony’s PlayStation-based ZN-2, so visually it represents a real upgrade. The 3D fighting remains familiar, though, although it upgrades its predecessor’s two-player teams to three-player teams, echoing Marvel vs. Capcom 2: New Age of Heroes.

This new team-based format unlocks some fresh gameplay opportunities, incorporating additional Team-Up attacks and the new super-powerful Party Up attack, which incorporates all three characters at once. Interestingly, this can be interrupted by a competitor, triggering a kind of “tag” mechanic, where the first player to get a hit in comes out the victor of the minigame.

While this version of the release lacks the board game campaign from the Japanese edition of the Dreamcast port, you can still choose between the arcade iteration’s Story Mode and Free Mode, with the latter locking you to the narrative arcs of the specific schools from the franchise’s lore. These have neat comic book panel cutscenes, which are extremely fun to absorb, even from a contemporary perspective.

Special mention must be reserved for the imagination of the character designs in Project Justice, and the Rival Schools franchise at large. Among the new additions here is Momo Karuizawa, a tennis player from Gorin High, and Yurika Kirishima, who fights with a violin.

The commitment to the series’ “school club” theme is ingenious, and it sets this franchise apart from other fighters, where you’re often controlling martial arts experts et al.

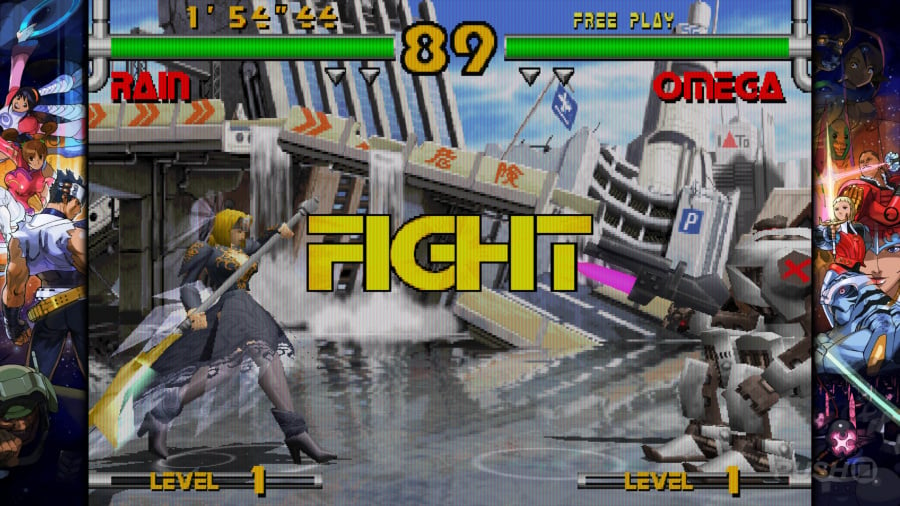

Even though it was eventually ported to the Dreamcast, Plasma Sword: Nightmare of Bilstein is one of the few games on this compilation – along with Capcom Fighting Evolution, of course – which doesn’t run on SEGA’s NAOMI chipset. Instead, interestingly, it’s powered by Sony’s PlayStation-based ZN-2.

That’s because predecessor Star Gladiator – Episode 1: Final Crusade was made with the PS1 in mind, at a time when 3D fighters like Tekken and Virtua Fighter were beginning to eat Capcom’s lunch.

The game was poorly received in its day, partly due to unfavourable comparisons with SoulCalibur, which is understandable considering Namco’s fighter looked several generations beyond what Capcom was offering here.

But while it does play somewhat similarly to the aforementioned weapons-based brawler, it does have some interesting wrinkles of its own, namely a striking Star Wars-inspired anime style and systems like the Plasma Field, which allow you to expend one level from your Power Gauge in order to put opponents in a kind of stasis and deploy character specific buffs, like growing in size or stopping time.

While it’s largely unremarkable, we do think there’s a je ne sais quoi to Plasma Sword’s archaic polygonal battles. And, if nothing else, playing this will help you to at least understand the origins of Hayato Kanzaki, a popular character in Marvel vs. Capcom 2: New Age of Heroes.